So far I’ve covered Shyamalan’s technical and thematic side in two different articles consisting of three films. Now it is time for his fourth, what I deem to be his magnum opus: The Village. When it was initially released, many were thoroughly disappointed and downright hated it. Shyamalan was fresh off the back of Signs, which overtime succumbed to criticism, was a massive financial success. It garnered positive reviews from critics (4/4 from Roger Ebert who conversely stated The Village was one of his most hated movies of 2004) and audiences found it quite thrilling and creepy. 2 years later the trailer for The Village drops, depicting it as a dark, scary horror movie about a 19th century village being assailed by enigmatic cloaked monsters. There were enormous expectations for it. Alas the marketing did not do the romance-mystery justice and viewers walked out disappointed. It may have snagged an Oscar nomination for Best Score for James Newton Howard (who has worked with Shyamalan on all his movies up until The Visit, but it was the beginning of Shyamalan’s downfall in the eyes of the public.

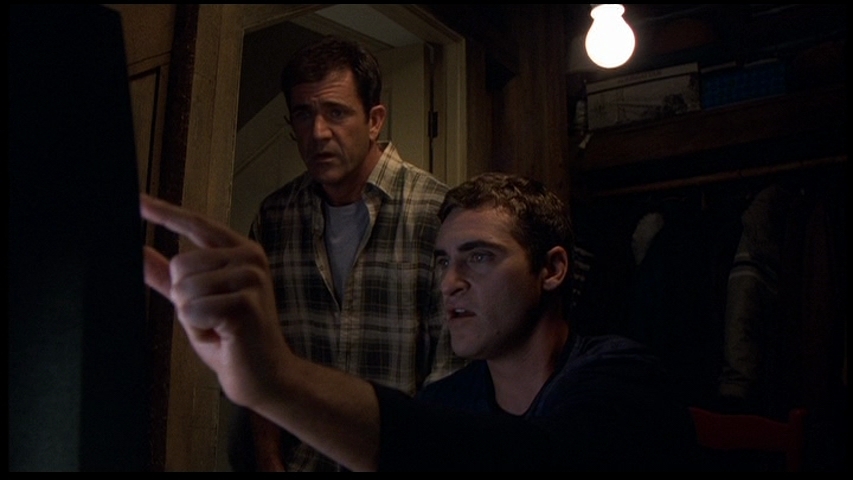

The Village was an ambitious project. It included Shyamalan’s biggest cast to date. Alongside Bryce Dallas Howard in her debut role, it starred Joaquin Phoenix, Sigourney Weaver, William Hurt, Adrien Brody and even a young Jesse Eisenberg (before he rose to fame). Aside from James Newton Howard, the crew featured the legendary cinematographer Roger Deakins (12 time Oscar nominee) and the Oscar nominated editor Christopher Tellefsen. The entire settlement where the movie takes place took eleven weeks to build, filming was mired by harsh winter weather and Shyamalan had to rewrite the script after it was stolen a year before the film was released and was published online. After that nefarious event he locked down all news coming out of it and filmed it in extreme levels of secrecy.

The lukewarm reception The Village received hides its rich, thoughtful underbelly laden with symbolism, metaphors, messages, crafted images, and much more. It’s difficult to know where to start, but as always when telling a good story, it’s best to start at the top.

MASSIVE SPOILERS AHEAD AS USUAL

In Shyamalan’s infamous twist, it is revealed Covington is not actually a contemporary 19th century village, but an artificial creation of the Council of Elders who attempted to escape the horrific experiences they endured back in the urban city centres. To do this they created a natural reserve, patrolled 24/7 by unwitting guards, payed off airlines to divert their routes around it, and started an entire society anew by themselves. Their children were raised without any knowledge of reality and coaxed into believing they actually live in a rural area of the 1800s. To prevent anyone from leaving, the chief Elder Edward Walker takes inspiration from a history book where he read about old legends of monsters stalking nearby woods. Costumes are fashioned and periodically the elders skulk around the edge of the glades to reinforce fear.

What makes the twist in The Village so different from those of Shyamalan’s previous movies is that it ultimately barely changes anything for the characters inside the film. Ivy is deliberately allowed to leave and return because her blindness doesn’t allow the truth to be exposed. There are no realisations to be had about what really exists beyond Covington Woods. The inhabitants continue to live in their deluded world, and the Elders continue to reinforce them. Even Ivy, despite the the monsters are just costumes will never know that Noah was actually the one who attacked her and instead will cling to the idea that the legends from which the creatures were derived from are real. After the movie ends, Covington will return to it’s previous state, even without Noah. The Elders have chosen to value everyone’s security over the truth. While it may seem Edward might have softened towards the taboo of outside contact, his motivations were arguably affected by both Ivy’s chance at building a loving relationship and Alice (Lucius’ mother) not losing her relationship with her son. As Edward states to Mrs.Clack

“… she is led by love. The world moves for love. It kneels before it in awe.”

Love is one of the major themes in The Village. It is found in different forms. We have Kitty’s unrequited love for Lucius, Edward’s confused love for Alice, Ivy’s and Lucius’ blossoming relationship, Noah’s worried and angsty love for Ivy, Ivy and Lucius’ caring love for Noah, Kitty’s sisterly love for Ivy, and the Council’s protective love for the population they are responsible for. It is what drives the film forward and shapes all of the decisions made for the entirety of it’s duration. Even when it might be violent or misguided and present painful outcomes, all deeds and events occurring are a direct result of affection. The irony is that it both binds and threatens to break the society within which it has been born out of. Lies are created, people are hurt, minds are locked inside themselves. On the opposite spectrum it causes people to shelter others and chases away loneliness while creating hopes of a better future. It’s a hard topic to pull off without feeling sappy, but The Village approaches it in a very mature manner.

One can argue that another, more sinister interpretation of the film, is that of post 9/11 allegory on the Iraq War and American society. The Elder’s are are representation of the US government and how it reacted following the 2001 tragedy. Every single Elder has been compelled to their cause by having to go through some type of loss. Corruption, robberies, rape, and suicide were all somehow intertwined when they used to live in the towns.They subsequently enclose the population in a series of questionable reports that are supposed to keep them safe from the terrors of the outside world. As for the terrors, or “Those We Do Not Talk About”, these are a combination of terrorist factions and weapons of mass destruction. They are based on stories, but may or may not be true. Of course this incites people to be vigilant and are more inclined to do the ruler’s bidding. The only way to protect oneself is to return to a time of purity and “national unity” where traditions are upheld to express solidarity. This sets back progress on a number of domestic socio-economic and developmental issues to instead focus on identity and external forces. To add onto that, by the time we learns the monsters are fabricated, society still doesn’t change. The less informed ones (Noah) have become indoctrinated and turn to violence. Ignorance turns Noah into one of the monsters. Unable to understand reality, he becomes a menace to both himself and others. The Village makes a statement about how stories can influence our way of living and falsify the very people we are.

With this in mind, it is a much more cynical movie that at first sight. By reconciling the existence of violence, crime and tragedy in the outside world with the goal of creating a simple and communal society, the Elder’s inadvertently fall victim to deception and hypocrisy. Stories are fabricated even though their original purpose was to enlighten. The Village is much darker than the other Shyamalan films because it supports the idea that one cannot lock evil out. Covington breeds its own tragedies despite attempting to be a safe haven. The movie opens up with the death of a seven year old child. While the cause of death is unknown, it is safe to assume it was preventable by Lucius’ perception of injustice. The Elders have refused to get help from the outside world because it would apparently compromise the collective safety of everyone. Ivy’s blindness was also preventable and her father chose to ignore it. Likewise it is not foolproof in terms of raising respectful and peaceful people. Noah suffers from some type of a mental disorder that impedes his ability to speak properly, perceive information and function as a member of a community. Again it is unknown whether his illness could be cured, but the Elders refuse to accept both that the possibility is true and that he should receive help. According to them the proper solution is to lock him inside a small house in solitude. Noah sadly never overcomes his demons and is left to fester in his inner hell. This drives him to commit murder and assault.

Going by this, Noah is a lonely soul. The very reason he commits his crimes is his loneliness and crude comprehensive skills. He feels for Ivy because she actually plays games with him and doesn’t resort to locking him inside his cell as soon as he misbehaves. She chooses to trust him. When Noah however find out Lucius and Ivy plan to get married, he fears that they will abandon him. Despite him seemingly liking Lucius’ company, he elects to remove him so Ivy can stay his. It also worthy of note that he doesn’t seem to want to kill Ivy when he encounters her in the woods. He rather wants to chase her back to Covington. Regardless of him thinking she will leave forever or save Lucius, the outcome for him is the same.

Noah isn’t the only lonesome being in Covington. Lucius himself, stoic and brave, often spends his days alone in the workshop. He finds it difficult to express his love for Ivy even after it forms its shape inside of him. This leads onto another theme in The Village, namely that of the difficulty of communication. Truth must be let out, yet it cannot. Noah’s speech impediment leaves him fool. When it comes to Alice, Edward is plagued by the ever present

“Sometimes we don’t do things we want to do so that others won’t know we want to do them”

Lucius himself is a victim of this as Ivy explains. It is through this very knowledge of mutual truth that Lucius knows Ivy feels his passion for her. Furthermore, at a similar point in the movie where the viewer finds out the lies surrounding the Walker Reserve, the locked boxes of pain are finally opened and the Elders face their inescapable traumas. Like all of Shyamalan’s good movies, there is a strong element of characters waking up to reality. Of course it is a different type of reality than we expect. Maybe this is the reason a large portion of the scenes are filmed from behind the character’s backs: to show them literally turning their back on the truth. Even during Ivy and Lucius’ conversation on her front porch, the fog in the background, Shyamalan never cuts to a side profile like other directors would. Instead the comes in closer from the same angle.

Past the metaphysical realm of The Village lies even more. I’ll round this analysis off with the visual components presented. First off is Shyamalan’s use of colour. Very clearly is the contrast between yellow or “the safe colour” and red. Yellow here is meant to represent all things good about Covington. The safety and innocence of the unwitting inhabitants. The red is the colour of the aggressor. The monsters wear it and it is painted upon the doors of the houses they’ve visited. Noah is seen with hands full of crimson blood, rocking in a chair. At the beginning of the movie a red figure is reflected in a puddle of water, towards the end the yellow colour is reflected instead in an almost identical shot. This symbolises the return of safety to Covington (Noah is gone). It is also worth noting how the teaching of the Elders have reached so far into the lives of the inhabitants that to the point of paranoia. Everything red is immediately discarded. Berries and flowers must all be removed as soon as possible else it will attract the monsters.

Another recurring topic similar is Lucius’ colour. While it is never explicitly stated, there are a number of clues that together make a convincing claim. It is interesting to note that Lucius on screen is always close to some manner of brightness. He is always next to either a source of light or a white-like colour. Even his name is a derivative of the latin lux/lucis or light. Edward tells Ivy she sees “light where there is darkness” referring to not only her hope, but Lucius himself. Ivy is only capable of seeing a few people through a sort of undefined haze. Among them are her father and Lucius. Both are strong characters: brave, strong, and resourceful. When Lucius is dying, Ivy cannot see him because those qualities are at risk.

The Village also draws comparisons with Psycho. Both feature director cameos in some relation with glass (Hitchcock outside a window, Shyamalan reflected). Both give the impression you know who the main character is, and turns that on it’s head when they are stabbed. The real main characters (Norman and Ivy) aren’t revealed until further in the story. Both also have two sets of twists. It also has some distinct Shyamalan trademarks I haven’t talked about. It has dialogue scenes with long-timed shots where we see a only a single character in frame, as well as a home invasion (beginning of Sixth Sense, climax of Unbreakable, aliens in Signs.)

I’d also like to mention a small note to the use of chairs, hands, and slow motion in The Village. There are many, many shots of them simply empty in a void environment. The meaning could extend to a form of grief, rustic life, or to danger (Noah) being on the loose. The only time we know where Noah is, is when he is sitting in a chair. When he is eating, in solitary, or rocking on the porch after stabbing Lucius. As for hands, we get explicit close ups on Ivy’s through the film. These are the tools she uses to sense the world around her, often they are turned palm-down, showing her caution. It is sideways, inviting for new information, when she touches the creature costumes for the first time. It is palm-up when she is reaching out to her beloved Lucius, and clenched firmly when grasping his hand as he leads her to safety. Shyamalan uses slow motion only in moments of danger, slowing down time as characters are in fear and under attack.

The Village teems with deep nooks and crannies under its beautifully lensed exterior. I’d like to round this off by recommending to listen to James Newton Howard’s magnificent score, and to let my readers bear with me as there is only one article left in my series of Shyamalan analyses.